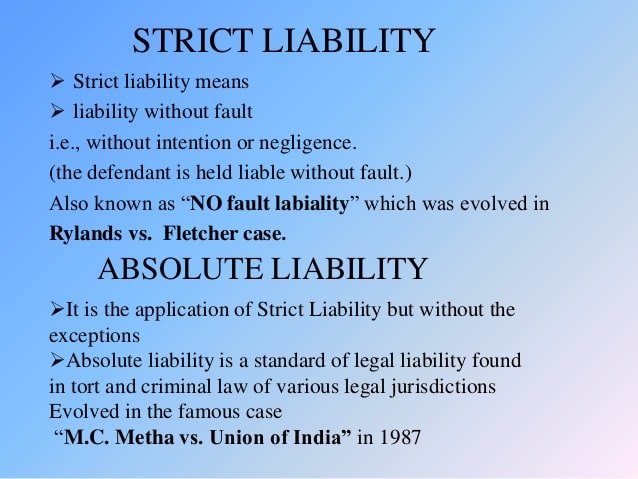

RULE OF STRICT LIABILITY AND ABSOLUTE LIABILITY

Rule of STRICT LIABILITY

According to Blackburn J. –”The person who for his own purposes brings on his lands and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief if it escapes, must keep it in at his peril, and, if he does not do so, is prima facie answerable for all the damage which is the natural consequence of its escape[1]“.

The principle of strict liability was evolved in the case of Rylands v. Fletcher[2]. In this case, the plaintiff builds up a reservoir in his land in order to power his mill, but accidentally the water flooded the adjacent coal mines of the defendant, which cause substantial damage to the defendant. The court held that defendant build a reservoir on his own risk and if any accident happened will be the sole fault of the defendant.

The principle laid in this case can be stated as; if a person brings any dangerous thing in his premises and if such dangerous thing likely to escape and cause damages, then the defendant will be liable for all the damages, even if there was no negligence on defendant part. The liability is imposed on him is not for his negligent act but for keeping the hazardous thing on the premises is sufficient to hold him accountable. The following condition must be satisfied to categorize a liability under strict liability.

- Dangerous Substance

- Escape

- Non-natural use of land

- DANGEROUS SUBSTANCE.

The defendant can be held liable only if a “dangerous thing “escapes. A dangerous thing can be termed as anything which likely to mischief when escape causing severe damages. The toxic gas, electricity, corrosive chemicals, even water stored in large quantity can be termed as dangerous.thing.

INTRODUCTION TO TORTS: Law of Torts- Our Legal World

- ESCAPE.

One more essential condition to make the defendant liable is the escape of the dangerous thing, and it must be out of the reach of the defendant for instance if poisonous plants plant growing on the defendant land escape and neighbour cattle died after eating it than the defendant will be held liable, but if the cattle somehow enter into the premises and died, then the defendant will not be held liable as there is no escape of the dangerous thing. In the judicial pronouncement of Reads v. Lyons & Co[3] if the dangerous thing doesn’t, escape no liability.

- NON NATURAL USE OF LAND.

To constitute strict liability, there should be non-natural use of the land. In Ryland v. Fletcher, the water collected for the functioning of the mill was considered a non-natural use of land, whereas water collected for domestic use was considered as natural use by the court. When the term “non-natural” is to be considered, it should be kept in mind that there should be some special use which creates danger. Supply of cooking gas or for instance supply of electricity for domestic use, which caused fire will not be considered as non-natural use of land.

EXCEPTION TO THE RULE OF STRICT LIABILITY.

There is a certain exception for strict liability.

- PLAINTIFF FAULT

If the plaintiff is at fault, whether intentionally or unintentionally placed himself in a dangerous situation, then the defendant will not be held liable. In the case of Ponting v Noakes,[4]The plaintiff horse died after eating poisonous leaf on defendant land. The court held that as it was the fault of the plaintiff, so the defendant was not to be held strictly liable for such loss.

- ACT OF GOD.

The phrase “act of God” can be defined as an event which is beyond the control of any human agency. Such acts happen exclusively due to natural reasons and cannot be prevented even while exercising caution and foresight.[5].The defendant would not be held liable for any accident which can not be foreseen by man of reasonable prudence or escape of any dangerous substance because of some unforeseen circumstances, will not be held liable.

In the case of Box v Jubb[6] where the reservoir of the defendant overflowed because a third party emptied his drain through the defendant’s reservoir, the court held that the defendant wouldn’t be liable.

- CONSENT OF PLAINTIFF.

If the plaintiff has given his consent whether implied or expressed to expose himself to the danger as in the case of volenti non fit injuria then the court will not hold the defendant liable for his actions. Where the plaintiff and the defendant are neighbours and share the same water supply on the defendant’s property, the defendant shall not be responsible for any harm done to the plaintiff as a result of the water collected. On the other hand, when a festival is held, and the display of fireworks causes harm to the audience, the organizers will be responsible because the show will not be considered to be in the benefits of everyone.

- ACT OF THIRD PARTY.

The rule also doesn’t apply where a third party act causes the damage. The third-party means that the individual is neither the defendant’s servant nor the defendant has any contract or power over his work. But where it is possible to predict third party actions, the defendant must take due care. Otherwise, he will be held responsible.

In the case of Box v. Jubb,[7] where the reservoir of the defendant overflowed because a third party emptied his drain through the defendant’s reservoir, the court held that the defendant wouldn’t be liable.

CASE LAW.

Crowhurst v. Amersham Burial Board.[8]

If the branches of a poisonous tree planted on the defendant’s land spread to the neighbouring plaintiff’s property, this leads to the escape from the defendant’s boundary or control of that illegal, poisonous thing and to the property of the plaintiff. Now, the problem arises, if the plaintiff’s cattle nibble on those leaves, then the defendant would be held responsible under the aforementioned law even though nothing was deliberately done on his part.

Charing Cross Electric Supply Co. v. Hydraulic Power Co.[9]

It was the responsibility of the defendant to provide water for industrial works, but they were unable to keep their hands charged with the minimum necessary pressure, which resulted in the pipeline bursting at four separate places, resulting in significant harm to the plaintiff as evidence—despite no fault of the defendant, held liable.

Green v. Chelsea Waterworks Co.[10]

The defendant corporation was under a statutory obligation to maintain the water supply running. A major portion of the line, burst without the defendant’s fault, filling the plaintiff’s premises with water. The company was found not to be liable because it was engaged in the exercise of statutory duty.

ABSOLUTE LIABILITY

In simple words, the rule of absolute liability can be defined as the rule of strict liability, minus the exceptions. In India, in the case of MC Mehta v Union of India[11], the law of absolute liability evolved. This is one of the most landmark judgements relating to the principle of absolute liability.

The facts of the case are that some of the oleum gas leaked from industry in a specific region of Delhi. Several people had been affected because of the leakage. On the rule of strict liability, the Apex Court then established the rule of absolute liability and ruled that the defendant should be responsible for the harm done without considering the exceptions to the rule of strict liability.

According to the absolute liability rule, if any person is engaged in an inherently dangerous or hazardous activity and if any harm is caused to any person due to an accident that occurred during the performance of such inherently dangerous and hazardous activity, then the person performing such activity shall be liable. This should also not be considered the exception to the strict liability statute. The rule laid down in the MC Mehta v UOI case was also adopted by the Supreme Court when it ruled on the Bhopal Gas Tragedy case. The Indian Legislature passed the Public Liability Insurance Act to ensure victims of these incidents obtain timely relief through insurance

CASE LAW

Bhopal Gas Tragedy / Union Carbide Corporation v. Union of India.[12]

This principle was upheld in the infamous Bhopal Gas Disaster that took place between 2nd and 3rd December 1984. Leakage of methyl-iso-cyanide(MIC) poisonous gas from the Union Carbide Company in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh has led to a major disaster, and more than 3,000 people have lost their lives. Land, flora, and fauna sustained heavy losses. The consequences were so severe that even now, children are born with deformities in those regions.

A lawsuit was brought in the American District Court of New York as the Union Carbide Company in Bhopal was a branch of the United States Carbide Company. Owing to no jurisdiction the complaint was dismissed there. The Indian government passed the 1985 Bhopal Gas Disaster (Claims Processing) Act and sued the company on behalf of the victims for damages. The court, which applied the ‘Absolute Liability’ principle, found the corporation liable and ordered it to pay the victims compensation.

Indian Council for Enviro-legal Action v. Union of India.[13]

A PIL filed pursuant to Article 32 of the Indian Constitution voiced petitioners ‘complaints over the existence of factories which caused large-scale environmental pollution and endangered the lives of villagers residing in the vicinity of the factories. This violated their right to life and freedom given under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution because they did not live in a safe environment. The Supreme Court initiated immediate action and directed the Central Government and the Pollution Control Board to take strict steps against the concerned industries.

CONCLUDING REMARK

The rule of strict liability and absolute liability can be seen as exceptions, an individual made liable only when he is at fault. But the principle governing those two laws is that even without his fault, a person may be made liable. It is known as the “no-fault responsibility” concept. Under these principles, the person responsible may not have committed the act, but he would still be responsible for the harm caused by the actions. There are a few exceptions in the case of strict liability where the defendant will not be held liable. Yet in the case of absolute liability, the defendant is granted no exceptions. Within the strict liability clause, the defendant will be held liable.

REFERENCES

- [1] Rylands v. Fletcher 1868) L.R. 3 H.L. 330.

- [2] Ibid.

- [3] [1947] AC 156 House of Lords.

- [4] (1849) 2 QB 281

- [5] http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/act+of+God/

- [6] LR 4 EX Div 76.

- [7] LR 4 EX Div 76.

- [8] (1878) 4 Ex. D. 5.

- [9](1914) 3 KB 772.

- [10] (1894) 70 L.T. 547

- [11] A.I.R. 1987 S.C. 1086: 1987 ACJ 386

- [12] (1991) 4 SCC 548.

- [13] AIR 1996 SC 1446.

![Tax Law Internship Opportunity at Legum Attorney [Chamber of Ashish Panday], Delhi [Tax Litigation]: Apply by 2nd November](https://www.ourlegalworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Legum-Attorney-Intern.png)